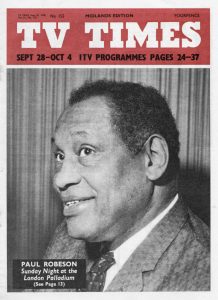

An interview with

SIR JOHN WOLFENDEN

Vice-Chancellor of Reading University, who is advising on the new ITV service to schools

From the TVTimes Midlands edition for 10-16 March 1957

School broadcasts on ITV in London and the Midlands are due to start on Monday, May 13, five days a week for an experimental eight-week term. And Sir John Wolfenden, Vice-Chancellor of Reading University, thinks this “could be the beginning of something quite big.”

School broadcasts on ITV in London and the Midlands are due to start on Monday, May 13, five days a week for an experimental eight-week term. And Sir John Wolfenden, Vice-Chancellor of Reading University, thinks this “could be the beginning of something quite big.”

Sir John is chairman of the 25-strong Educational Advisory Council established by Associated-Rediffusion, programme contractors for London weekdays. The new schools programmes arc also being screened by Associated TeleVision in the Midlands.

Sir John told me: “I don’t want to pretend that I am an expert on television. Nor do I want to say that I know nothing about it at all.

“I am certainly not one of those people who say or think that television is something you can’t touch with a barge pole especially Independent Television.

“I read a few weeks ago that a headmaster in Manchester had said that a television set would enter his school only over his dead body.

“This gentleman is a very dear friend of mine. But I wouldn’t think his opinion is typical of what people in schools think these days.”

Sir John continued: “It’s fairly obvious, isn’t it, and most people recognise, that a great deal of the derogatory things being said about television now is exactly what people said about sound broadcasting 20 or 30 years ago.

“And I should think that it is very clear from the consequences of sound broadcasting that there will be comparable benefits from television.”

Of the experimental eight-week term of school broadcasts Sir John said:

“I think this could be the beginning of something quite big. Depending, very much indeed, on how it is done.

“What we on the Advisory Council and the School Broadcasts Committee are trying to do is to give what help we can, of a background kind, to Boris Ford (Head of School Broadcasts) and Rosemary Horstmann (Assistant Head). I think it would be an awful pity for this council to get too much involved in the executive part of it.”

Sir John’s Council will be asked to advise on the educational implications of any of the company’s programmes

He said: “I think Associated-Rediffusion genuinely wants advice about a lot of programmes, but it’s over the school broadcasts that the thing has come to a focus. I think there is a good deal, besides these, on which it would be not improper for education people to have views.”

The council, said Sir John, is not entirely a teachers’ body.

“There are members from all ranges of the educational world and people who are interested in school-age children but are not professionally involved in teaching people from boys’ and girls’ clubs and youth organisations. I think that is very relevant to have people whose contact with school-age children is outside school.”

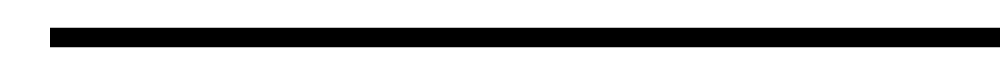

The broadcasts, initially, will be directed to the 14- and 15-year-olds, 75 percent of whom attend secondary modern schools.

Much of Sir John’s educational experience has been with public schools and universities. As the former headmaster of Uppingham and Shrewsbury, did he consider himself the right person to advise on broadcasts to secondary schoolchildren?

“Well, I would have qualms if I were the only person doing it. There are, of course, people on the Council and Committee more familiar with secondary modern schools than I should presume to be.

“As chairman, all I’m there for is to hit them over the head if they talk too much.”

If Sir John were still the headmaster of a public school, would he use television broadcasts ?

“I certainly wouldn’t rule them out. We did use sound broadcasts, of course.”

He supposed that the Committee would be asked what they thought of the general treatment that Boris Ford was suggesting:

“But it isn’t expected of the Committee that it will vet each programme, because that would stultify the people on the production side.

“You can’t have a programme put on by a Committee.”

The fact that the school broadcasts would be transmitted in the normal way, not on a closed circuit, might mean — I said— that they will be seen by viewers at home.

Sir John said: “I hope very much that they will look in. But I think that it would be blurring the thing if that audience were kept in mind when preparing the programmes. You must stick to your objective. But the viewers are very welcome to eavesdrop.”

The five-point programme

“There is no doubt in my mind that these programmes will present something of great value to schools, and in particular to school teachers.”

Those were words of Mr. Paul Adorian, managing director of Associated-Rediffusion Ltd., the London weekday contractors, when he presented to a Press conference the charter for the company’s school television broadcasts.

“It is not our intention to try to replace the schoolmaster. We are trying to give him some help in carrying out his work.”

It is planned that the subjects to be covered half-an-hour a day early in the afternoon will be:

Looking and seeing: A series to encourage children to realise how little and how sketchily they look at the world about them, and how to practise attention and discrimination.

A year of discovery: In 1957, the Geophysical Year, to explain simply the reasons for the struggle towards scientific achievement; to study the launching of the satellites and the Antarctic explorations.

A literary programme: To introduce a Dickens novel, alive and exciting, with the hope that many of the children will read it subsequently.

People among us: Programmes to introduce some of the immigrants now in Britain, and to make the point that Britain has for many centuries been enriched by receiving foreigners into the community.

On leaving school: A series to help children across the bridge from school to the adult world, and give them an idea of the problems and responsibilities involved.

Mr. Adorian added: “When we undertook to provide ITV programmes for five days a week, we undertook to provide a balanced service. Some of us think that a balanced service should include, school broadcasts.”

The Educational Advisory Council will advise Associated-Rediffusion on the educational implications of any of the company’s programmes, either at the request of the company or on the initiative of the Council. From the membership of the Council there has been elected a smaller committee to deal specifically with the new school broadcasts. This committee is also under the chairmanship of Sir John Wolfenden.

Other members of the Council are:

Mr. F. C. A. Cammaerts, Headmaster of Alleyne’s School, Stevenage; Mrs. H. R. Chetwynd, Headmistress of Woodberry Down Secondary School, London; Mr. John Gilbert, Head of Department of Telecommunications, Northern Polytechnic, London; Dr. J. A. Harrison, Director of the Educational Foundation for Visual Aids; Mrs. Molly Harrison, Curator of the Geffrye Museum, London; Mr. Fielden Hughes, Headmaster of Queen’s County Secondary School, Wimbledon.

Mrs. B. M. Humphrey, hon. sec., National Federation of Parent Teachers’ Associations; Miss E. M. Kimsey, Headmistress of Sydenham County School, London; Professor M. M. Lewis, Institute of Education, University of Nottingham; Dr. J. Macalister Brew, Education and Training Adviser, National Association of Mixed Clubs and Girls’ Clubs.

Professor Ben Morris, Institute of Education, University of Bristol; Mr. Deryck Mumford, Principal of the Cambridgeshire Technical College and School of Art; Mr. Paul Reilly, Deputy Director of the Council of Industrial Design; Mr. Albert Rushton, formerly Assistant Professor of Electrical Engineering, Imperial College; Mr. Percy Walton, Youth Employment Officer, Worcestershire; Dr. Simon Yudkin, Consultant Paediatrician, Whittington Hospital, London.

The following organisations sent representatives to the inaugural meeting and were invited to nominate permanent representatives: The County Councils Association; Association of Municipal Corporations; Association of Education Committees; London County Council; National Union of Teachers; Joint Committee of the Four Secondary Associations; National Association of Head Teachers; and Association of Teachers in Technical Institutes.